The further you get from training the easier it is to lose sight of the usual timeline for applying to residency. The Medical New Year has passed and it is now time for fourth year medical students to apply to residency. Over the past couple years, I’ve had the privilege of speaking with many students interested in pursuing IR and I’m often asked what to look for in an IR Program.

It is important to have an end goal in mind and work backwards to connect to dots. Of course, hindsight is 20/20 and it’s much easier for me to advise students now having been through the process, albeit in a somewhat different time, and having had the unique experiences I’ve had as an early-career attending.

The other thing I’ve come to realize is that no training program is perfect, particularly within the context of a very heterogeneous and ill-defined field as interventional radiology. If one is looking to become an IR Hospitalist, the most common practice pattern for interventional radiologists, I’m not sure where you train necessarily matters. For those interested in practicing 100% interventional radiology in a longitudinal clinical fashion I think there are certain things to look for in training programs which can help guide you in your decision-making process.

I am extremely grateful for my training, but it was far from perfect. I was trained to be an exceptional hospitalist and diagnostic radiologist. I think even with the integrated program, this is still largely the case and while it’s easy to get upset about it, it’s largely a reflection of our culture growing up within a radiology ecosystem. My personal bias is that working within a radiology context is flawed and we need to move beyond that. How do we do so? It all begins with training.

What are the essential components in developing the essential tools necessary to make it as an image-guided surgeon? There are five key areas: imaging, technical, clinical, business, mindset.

Imaging

Imaging training in the new integrated program has been reduced to 36 months to accommodate for the increased time on interventional radiology and associated clinical disciplines when compared to the old way of doing things where total time on IR constituted 12 months of fellowship and 3 months during residency.

Why is imaging training important? Two reasons.

1. Imaging is essential to understand anatomy and facilitate performance of image-guided interventions.

2. As a hedge.

The first reason is quite obvious, but no one seems to talk about reason number two. Simply put, there are very few jobs out there for the graduate looking to practice 100% IR in a longitudinal clinical fashion. And yes, the longitudinal clinical fashion part is important because the majority of 100% IR jobs are trash collection opportunities with healthcare system or radiology group subsidization.

Will the IR residency itself change this? My opinion is it won’t. This reflects reimbursement, culture and the overall healthcare landscape we exist in.

What will change things however are motivated and passionate graduates going out into the world and creating practices and subsequent opportunities for others. I suspect a fair number will not want to go down this road given the proclivity of medical school to attract risk-intolerant individuals who like following prescribed paths to career success.

So how will you make a living having devoted all this time to obtaining a unique skill set? Well whether or not you decide to be entrepreneurial with your future endeavors, you will more likely than not need your diagnostic radiology skillset to make money. This means you should be highly motivated in obtaining great training and learning how to become efficient.

For the interventional radiologist, most practices do not expect you to be a wizard at all of diagnostic radiology. One should focus their efforts in training on being an exceptional emergency radiologist and body radiologist as these are the areas which tend to be most pertinent to what we do and happen to reflect the needs and expectations of most practices. With only 36 months on diagnostic radiology, and with several of these months being what I perceive as somewhat wasted time (my apologies to breast imagers), you will need to be very proactive in obtaining training.

What should you look for in a good radiology training program?

1. Volume.

2. Autonomy

3. Didactics

You need reps (volume). You need opportunities to screw up (autonomy). You need people to teach you essential things, a lot of which is minutiae to help pass your boards (didactics).

To best assess for resident autonomy, find programs where trainees still take independent call. This is something that is harder to come by given demand for 24/7 attending emergency room coverage. I had independent call during training at a quaternary care center, VA, children’s hospital and a busy county hospital. I think more than any fancy-pants subspecialty exposure or big-name attendings reading me out during the day, simply taking independent call at night in diversified settings and being provided many opportunities to screw up set a strong foundation for my future career. It was painful, and embarrassing at times, particularly being surrounded by so many people smarter than me, but it made me better.

Everyone has different learning styles. Some programs may be more didactive heavy. Others may be more service heavy. At the end of the day I think most programs will get you to where you need to be. Besides, we all get to a similar point a few years after training.

Technical

I think too much emphasis is placed on technical aspects of training.

Getting good at cases is all about reps and perfect practice. Just like anything else in life. We all come out of training with variable degrees of ability, but after 3-5 years, most will end up in a similar spot provided you have ample opportunities to learn and improve.

The biggest point I’d like to make is that the number of cases one does is not important. What is the point of a trainee or graduate bragging about the 1,500 cases they did if more than 1000 of those were things like paracentesis or abscess drains?

When it comes to technical abilities, I think it is good to have broad exposure. I break it down as follows:

1. Trash collection

2. Interventional Oncology

3. Digestive Diseases

4. Musculoskeletal

5. Men’s Health

6. Women’s Health

7. Venous Disease

8. Arterial Disease

Most programs will be fine in teaching you the “bread and butter”/trash-collection which will likely constitute the highest volume of procedures you will perform. Most places will have sufficient exposure to interventional oncology and digestive diseases (think anything biliary or portal hypertension related).

The rest is what will differentiate programs, with the biggest differentiator being arterial disease. It is tough to get exposure to aortic and peripheral vascular disease within the IR division in the vast majority of programs. At the very minimum, you want to make sure trainees have exposure through off-service rotations.

Ideally, it would be nice to have arterial disease exposure in IR, but spoken from someone who was farmed out to vascular surgery in fellowship for this experience, I ended up ok. Of course, a lot of this had to do with me being extremely proactive and going through some extreme measures to help shore up perceived deficiencies post-training. It’s not the end of the world in the likely scenario that you don’t get great exposure to this in training, as sad as that is when it comes to our field and the “loss of turf.” You will likely have some deficiency somewhere and that tends to be more the norm than the exception. We all are forced to learn new skills after training.

When looking at programs, look for graduated autonomy. See the residents in action. You’ll quickly get a sense of which programs get the job done and which are still a work in progress.

Clinical

Not nearly enough emphasis is placed on clinical training. Looking back at my experience, this was the number one deficiency in my training and something I am working very hard to this day to improve on.

On the whole, I think the vast majority of interventional radiologists, including the majority of those program directors responsible for overseeing integrated IR residencies, largely underestimate the importance of clinical training. Our ability to be clinical has significant implications when it comes to choosing how we would like to practice post-training.

While everyone and their dog wants to wax poetic about their strong “Clinical IR” presence, the problem is no one knows exactly what this means. I took a crack at defining this a couple years ago, but I think even my initial attempt was somewhat lackluster.

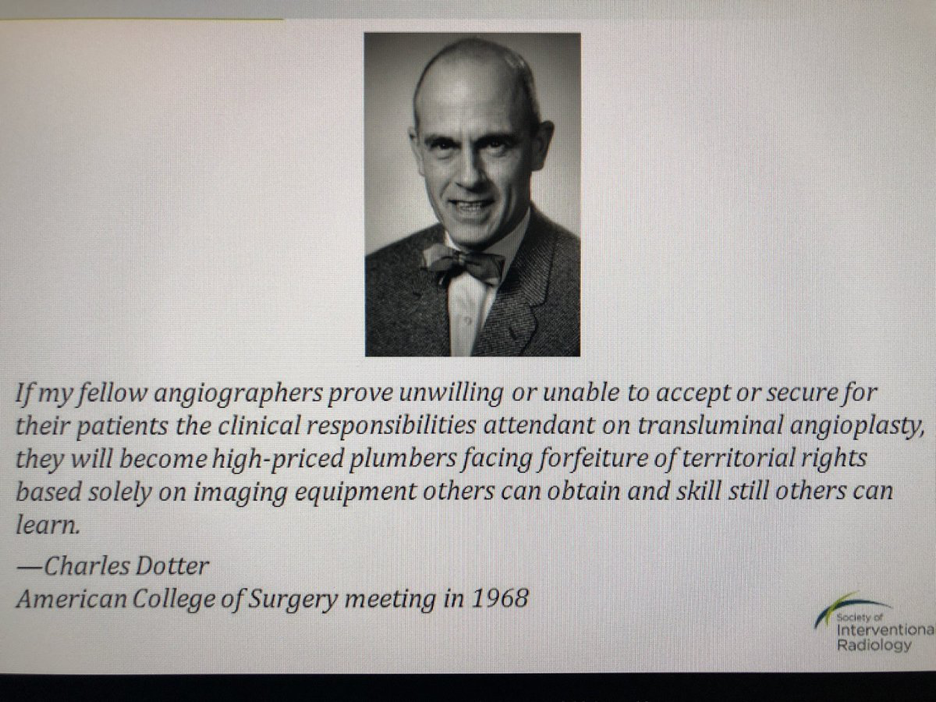

In order to better understand the depth of clinical experience one should likely strive for, I want to introduce you to a good friend of mine, the IR Evangelist. The IR Evangelist may or may not be a fan of Jesus, but they sure are a fan of Charles Dotter, the father of IR.

The IR Evangelist believes clinical training is the most important part of training. They advocate owning the disease process from start to finish. Think IR is an 8-5 job? Not for the Evangelist. The IR Evangelist believes IR is a 5-8 job. Practicing in a longitudinal clinical fashion is a moral obligation and has to be priority number one.

I think it’s rather easy to make fun of the IR Evangelist because on the surface it all sounds so ridiculous. How sustainable or realistic is a life where one is managing blood pressure in the clinic and rounding on all patients every day, particularly considering the lack of infrastructure and financial support for this structure in most practice settings. It requires a level of commitment and purpose above and beyond what it is expected of the average interventional radiologist. Can the jack of all trades really also be the master of all trades?

Probably not as a solo-practitioner living on an island by oneself (more on this in a future post), but why not strive for excellence? Once upon a time, I used to think that this was ludicrous. But as I got into practice and became more engrossed in the proposition of an independent IR practice it became abundantly clear to me that I needed more Dotter in my life.

Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.

It took me having an interventional cardiologist handing me a stethoscope to evaluate for aortic stenosis and carotid disease in CLI patients and also being forced to work-up undifferentiated self-referred patients for PAE and UFE in the OBL for me to realize that my clinical training was woefully inadequate and my ability to survive in a competitive healthcare marketplace as an independent IR was limited. I have since devoted a significant time to learning what I wish I should have learned over 5 years ago.

All too often, “multidisciplinary collaboration” is thrown around like a cute catchphrase to sound like a team-player, but the reality is it is a convenient way to mask our clinical deficiencies. Not every PAE or UFE referral will be handed to you on a silver platter by a urologist or gynecologist. In fact, I’d argue that depending on subspecialist referrals for procedures is a recipe to remain a trash collector for the rest of time. Not every wound patient will have arterial disease or venous disease. What’s the point of your beautiful “fill goals” doing vertebral augmentation if you don’t know how to medically manage the osteoporosis?

The fact of the matter is Crazy Charlie is right. How can we survive as physicians if we can’t take care of patients? More importantly, is it even fair to patients to operate on them if we aren’t able to fully take care of them in a longitudinal fashion?

Is living a life of comprehensive clinical management across all disease states in an inpatient setting reasonable for everyone? Probably not, but the fact of the matter is the training is invaluable when it comes down to having all the tools necessary to comprehensively manage patients so we can be their doctor and serve as a clinical gatekeeper. Ultimately this paradigm is essential for promoting a future of IR independence.

So if I were a trainee, I would do the following, full on acknowledging that it will be painful and unpleasant for some, but temporary:

1. Surgery preliminary year

2. IR program with a strong clinical presence.

What constitutes a strong clinical presence?

1. Rounding service staffed by attending physicians, and not just APPs reporting to attendings in their offices or control room.

2. Longitudinal IR Clinic, attended by trainees at minimum twice a month regardless of current service obligations.

3. Faculty actively competing in the “Red Sea” of arterial disease and not just the “Blue Sea” of embolotherapy which will become a Red Sea in due time

You want to know the dirty truth? There are very few programs like this. Want to know an even dirtier truth? The majority of you probably want to do IR to develop a procedural skill set with a perceived lifestyle advantage compared to surgery, just like many of your faculty before you. Not a great recipe for success. If this is you, I’d suggest not pursuing interventional radiology because we need to move away from this direction in order to advance.

Traditionally even the most historically “clinical” of programs treats their trainees mostly as technicians with their attendings acquiescing to the needs of referring clinical services in order to avoid political battles.

I think there is a true dearth of IR Evangelists in academic and private settings. Being an Evangelist is hard. It’s clearly the road less traveled. I empathize with their plight because in many ways they are trying to exist in an ecosystem that isn’t designed for them. Try to find an evangelist and learn from them. Whether or not you live the life of an IR Evangelist tasked with training responsibilities is one thing, but I think you will be far better off learning with one than without one.

What if you can’t find an Evangelist? Well, you kind of have to be one for yourself and others around you. This means being a self-starter and understanding the long game. If you’re being farmed out to other clinical services, focus on the clinical management of disease states. Go to their clinic and just soak as much information as you can. It will make all the difference when you’re out here with your livelihood dependent on it.

Business

Your training in today’s healthcare landscape is absolutely nothing without an understanding of basic business principles. This is what you need to know:

1. Practice-Development

2. Basic Healthcare Economics

3. Relationship Management

What’s interesting about these three concepts is they all have business corollaries. Practice-development involves sales, marketing and client-resource management. Basic healthcare economics involves understanding general accounting and finance principles. Relationships come down to understanding organizational structures and learning to listen more than talk. Not understanding politics, which is really just a function of relationships and power-dynamics, can derail even the most talented and hard-working of IRs. Believe me, I’ve been there.

Granted, while a lot of this information you’ll have to learn on your own after training, the concept of practice development is very pertinent to IR program development and trainee education. Very few educators in IR involve their trainees in practice development such as establishing professional relationships with trainees of other departments and being engaged in efforts to introduce the management of new disease states into the existing practice. It’s a true shame because many young faculty are tasked with developing new service-lines which should be a great opportunity to involve trainees.

If I were in an interview, here’s a simple question I would ask the IR division chief: what opportunities are there for trainees to help grow the IR service? See what they say and comment on this blog post. I’m legitimately curious.

Mindset

The more I practice medicine, and the more I reflect on my path, the more I realize every day that our mindset dictates everything. I’ve been guilty of having a poor mindset for many years. In fact, I’d argue that most of us in medicine could use a mindset readjustment.

We are always trying to get to the next step: college, medical school, residency/fellowship, then finally a job. Even then we continue to hustle our way into partnerships, promotions, committees, industry KOL positions and more. But why? What’s the point? I’d contend that most are probably not happy, but are just wired to be mindless hamsters spinning the wheel in perpetuity until their retirement or eventual demise. A bunch of lemmings. Don’t be a lemming.

Even for those who step back and are weary of this prescribed framework or faulty idea of success among many academic IR luminaries, the general landscape of medicine with a regulatory environment that has promoted rapid consolidation has done nothing but erode autonomy and purpose among many well-intentioned and passionate physicians. It is so hard to not be negative about our future. How can one ever be happy practicing medicine?

I think one way to do so, despite the harsh realities I constantly point out on this blog, is being around passionate, intelligent and motivated people who push each other to get better every day. It’s all about having a growth mindset. What you know is not nearly as important as taking the steps necessary to get to where you want to be. You need to be around other people who feel the same way in order to reach heights which you did not think were possible.

If I were a trainee, I would identify programs with faculty who have this mindset. The faculty who think this way are ones who are truly happy practicing as an image-guided surgeon. Oftentimes their attitudes will be contagious. It will be so obvious when you are around someone like this. All of a sudden, those long painful days on service may not seem so bad or painful.

I often find myself feeling this way when I’m around a group of people who are just as fired up about things as I am. There is something about being around other people who share common interests which will motivate you to work harder. By spending time with other trainees in any given setting you’ll see very quickly how much pride they take in their work, what their interactions with their co-residents are and how happy many are in a given setting. Their well-being very well may reflect the vision and mindset of the IR division chief or department chair.

Avoid places where people are unhappy, regardless of the name. Avoid places where you don’t connect with the division chief or program director, regardless of how big their name or reputation is. I remember interviewing at a big-name fellowship and avoiding it like the plague because I thought the program director was a jerk. I didn’t rank the program. No regrets. Your happiness matters more than a name on your resume which most people won’t care about in a few short years. Part of adjusting your mindset is realizing that what you do when you get to training matters a whole lot more than where you trained. Choose wisely.

Conclusion

I want to wrap up this post by addressing some common questions which come up in my discussions with students:

Should I rank reputable DR programs over integrated programs which are strong in IR but perhaps not as strong in DR?

Being perceived as “strong in IR” tends to have very little to do with what really matters which is the strength of clinical training. If clinical training is questionable, I’d opt for the longer path of training at a reputable DR program followed by ESIR or two years of dedicated IR training. If there is good clinical training in the integrated program with solid faculty, I’d rank that first.

Does my choice of residency impact my job prospects?

Yes and no. Private practice IR/DR jobs (trash-collection opportunities) come in a couple flavors: private-equity owned (bad) and independent radiology group (not as bad). “Good” independent radiology group jobs tend to be local/regional and are usually filled via word-of-mouth. If you know you’re headed down this path, then choosing a strong local or regional program with connections will probably serve you better than going to a place which may be perceived as “higher ranked” among academics but is in a location remote to your future destination. Of course, keep in mind that some large programs have robust alumni networks which may make geographic location of your actual residency not as important. Best thing to do is to get to know the practices before matching and express an interest as early as possible.

If you’re headed down a path of independent clinical practice, then go to the program offering the best clinical training.

What if I’m not sure if I really want to do IR yet?

Do you enjoy radiology? If yes, go do DR. If no, avoid IR and go do something else. It’ll make your life less complicated. If any of you IR attendings disagree with this, it likely means you’re an IR Apologist.

I’m hellbent on living the OBL life. Where should I train?

Go to the program offering you the best clinical training. The best clinical training does not mean the one “doing the best cases.” Some trainees and faculty like to “Twitter-brag” about the sweet work they’ve been doing. Congratulations, your department did 5 Y-90s yesterday. While that’s cute, what’s more impressive to me is understanding how those referrals were generated and the actual clinical work that was put into taking care of those patients. Those skills will set you apart. Being a technical wizard alone will not get you very far. And let’s be brutally honest. Those Y-90s likely came about because of some tumor board recommendation. Read this older post to get a better sense about how I really feel regarding this matter.

If you’re going down the OBL path, also please make sure you work hard to develop your imaging skills. Go someplace where you can moonlight DR so you can establish a strong financial foundation for yourself before taking the road less-traveled. It is possible to maintain DR skills without being part of a radiology group post-training.

Some final words before I conclude this post.

1. It’s a small world. Treat everyone you meet with respect even if they don’t reciprocate. Try to make as many contacts as you can and do your best to keep in touch with people. I’m often surprised how frequently I reconnect with people I met as a medical student, but have not had much interaction with while training in different programs.

2. Most IR programs will have significant deficiencies. The perfect program doesn’t exist. The biggest names aren’t necessarily the best places. The best place for you may not be the best place for most people.

3. My perspective is based on my own unique background and experiences. Please obtain many different perspectives before making any life-altering decisions.

On my first day on service as a DR resident years ago, a wise elder attending said, “read as much as possible every single day during residency…it’s invaluable time and you won’t have that time after you finish training.” Definitely didn’t heed that advice as much as I should have. For the IR trainee though, especially those in programs less “clinical”, you absolutely need to spend quality time off service with GI, surgery, vascular, pain, urology, gyn, onc literature in order to have a decent working knowledge at the minimum. Use each and every case you’re exposed to in training as a learning opportunity. It definitely gets harder trying to do that post training.

Truly excellent post. Kavi has nailed it. Clinical training is most important. At UCSD under Eric Van Sonnenberg, a body IR pioneer, we rounded EVERY morning on every patient we had performed an IR procedure on until they were discharged. 40% of our referrals were obtained simply by seeing other speciality physicians on the floors while rounding! We were one of “them”. We also had one of the first IR clinics in the country at that time. This mindset has made all the difference in my career. Most IRs are trained to be technicians and have no clinical mindset.

Much to comment on Kavi’s post but it is all golden information. Regarding mindset: In life, you are who you associate with so be very careful!

i agree with all especially ‘mindset’- training with like minded people makes the ‘work’ fun. staying late for cases becomes interesting and not as onerous (waiting for transport)

one more question to ponder- why can’t highly motivated IR trainees do 2-4 week externship rotations at existing OBLs or other established IR vascular centers? ones that already do 100 percent IR work, high level cases, clinic every day, longitudinal care?

Just because most academic programs lost the battle for real vascular work (PAD and veins) doesnt mean we cant train our own IRs in our own OBLs.

Last comment- could there ever be a better time to abolish pseudo exclusive contracts as a society? Imagine sharing a larger IR call pool, negotiating our own hospital contracts, sharing an OBL. trainee education would also improve with this! as you have said major change is necessary and i think it may take our younger generation IRs to DEMAND it to happen

Any recommendations on which programs meet this type of criteria?

It has been over 6 years since I’ve looked at fellowships. Even my own residency (UCSF) and fellowship (UNC) have changed drastically over this time with new faculty, leadership etc. I encourage every reader to do their own due diligence beyond the internet. You need to talk with current trainees and recent grads (within the last 1-2 years) to see what they think. One program that stands out to me as unique in a very positive way is the Kaiser VISLA program. Listen to https://www.backtable.com/shows/vi/podcasts/240/changing-vir-training-paradigms. I’d look for programs like this, but keep in mind they are rare. You will likely not end up with ideal training. Better to acknowledge that now and do what you can to fill gaps in your early career.